Walking, Talking, Teaching, and Learning: The Staff Ride

Introduction

Military history’s breadth and depth are expansive, and its practitioners are daily reshaping and increasing its intellectual and pedagogical scope. Our subdiscipline is dynamic and draws upon other fields within history and other disciplines from geography, demography, the sciences, to literature, and more. Military history ranges from traditional operational military history with its focus on strategy, tactics, weapons, geography, doctrine, and the other related elements, to war and society, how war, warfare, and their associated activities affect and are affected by societies. As in all scholarly fields, there is a healthy discussion over the nature and extent of what constitutes military history, and at its best this helps impel the creative, intellectual, and pedagogical processes. Most of us who teach military history do so in the classroom. Ideally, this teaching extends to archival research and introducing students to the processes and craft that underpin history. Colleagues in public history, particularly those who work at battlefield parks and museums or sites like the National Park Service’s Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, teach primarily to the interested public. Like those in the formal academy, public historians are deeply read in the historiography of their subject areas and have spent many hours interrogating the evidence from archival research. [1]

It is here, at the intersection of academic and public history that the staff ride emerges as a singular method for teaching military history. Battlefields, campaign areas, and the locations associated with them, the manufacture and distribution of war materials, prisoner of war camps, hospitals, and much more become the classroom and primary evidence for interrogation and exploration. There is nothing quite like walking, talking, and examining war-related sites to develop a finer appreciation for some of war’s contingencies, and the actions, decisions, understandings, limitations, and opportunities that past actors encountered. Originally conceived as an element in officers’ professional military education in the nineteenth century, the staff ride has much to offer all students and teachers of military history. [2]

In January 2006, after having spent the past eight years teaching undergraduates, and having served as a department chair, and program head, I surrendered a tenured position to become a historian on the Staff Ride Team at the Combat Studies Institute, US Army Combined Arms Center, at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The next six years were among the most enjoyable and insightful in my career as a historian and teacher. I left the team in January 2012, after having served briefly as Chief, Staff Rides, to accept a position at the School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College. Despite having returned to the classroom, I still design and lead staff rides (and tours), but far more importantly, the skills and thought processes developed from those six years on the staff ride team play a profound effect on my teaching, my research, my writing, and my understanding and analysis of war and warfare, and their cultural and societal interplay.

My initial work as a military historian was solidly within war and society, wherein I had written a cultural and intellectual history of soldiering in the United States, For Liberty and the Republic: The American Citizen as Soldier, 1775-1861. I had visited battlefields before, and had led students to them, but I had never fully grasped or appreciated how to integrate them into my teaching or my students’ learning. In retrospect, this was more than a bit embarrassing. I had served as an armor and cavalry officer from 1983-1987 in the California Army National Guard, then on active duty in the Republic of Korea and at Ft. Hood, Texas. The army had trained me how to read maps, analyze terrain, estimate distances, and a host of other skills, but it was not until I joined the staff ride team and paid my first visit to Gettysburg as a member of the team that I began grasping something of this powerful teaching technique. [3]

A Gettysburg Moment

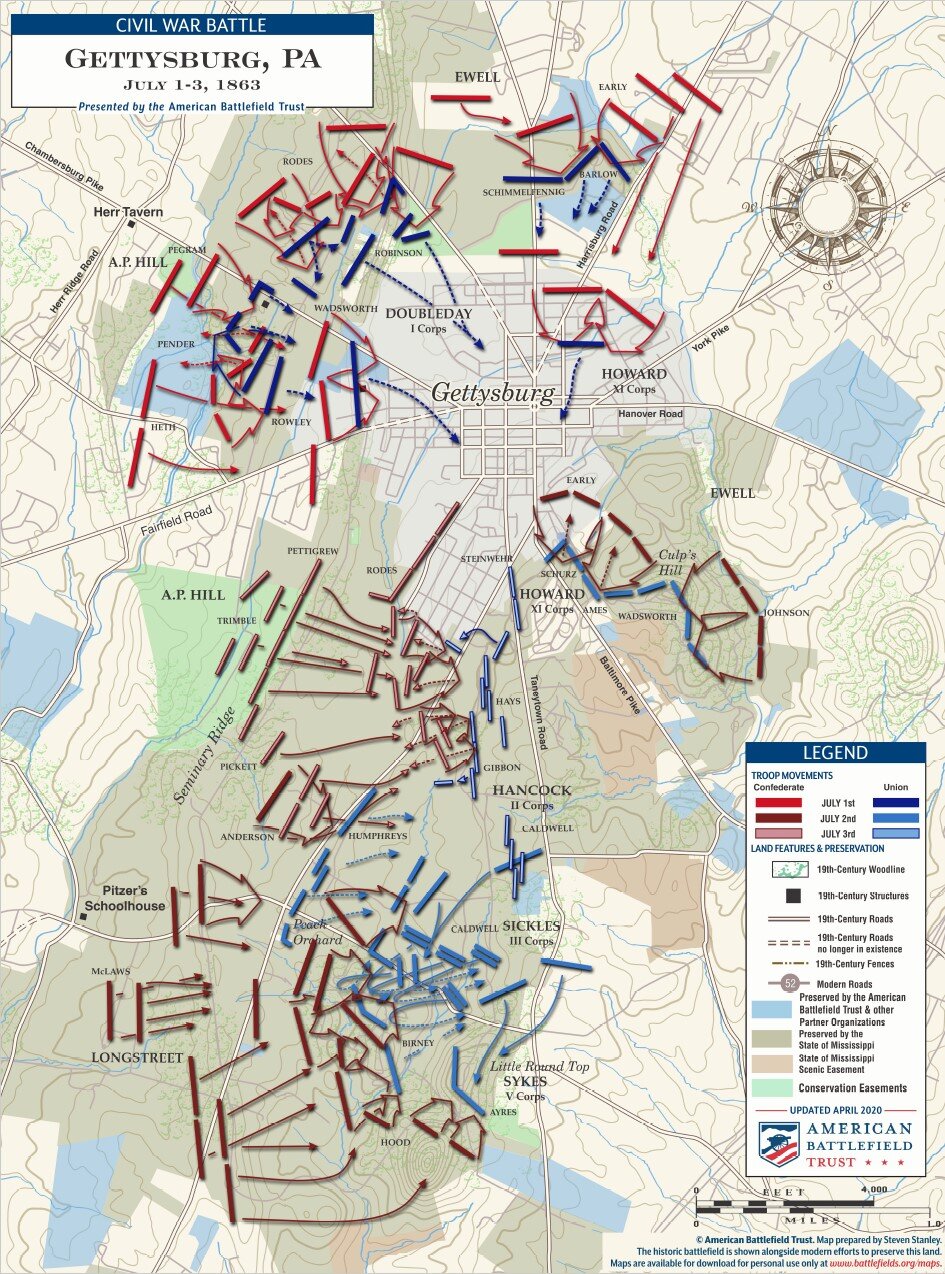

My moment occurred in the spring of 2006 while walking the US line along Cemetery Ridge, tracing the line of battle that Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps held on 2 July 1863. Second Corps’ line ran from the southwestern face of Cemetery Hill, facing west, south to about where the New York Monument today stands. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commanding the Army of the Potomac, ordered Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles to tie the right flank of his III Corps with the left flank of II Corps, and to extend his own line southward, to the crest of Little Round Top. Hancock’s three-division corps, some 11,000 soldiers strong, occupied a low but pronounced ridgeline of about three-quarters of a mile. Sickles’s two-division corps was to hold a line just under one mile long with around 10,000 soldiers. [4]

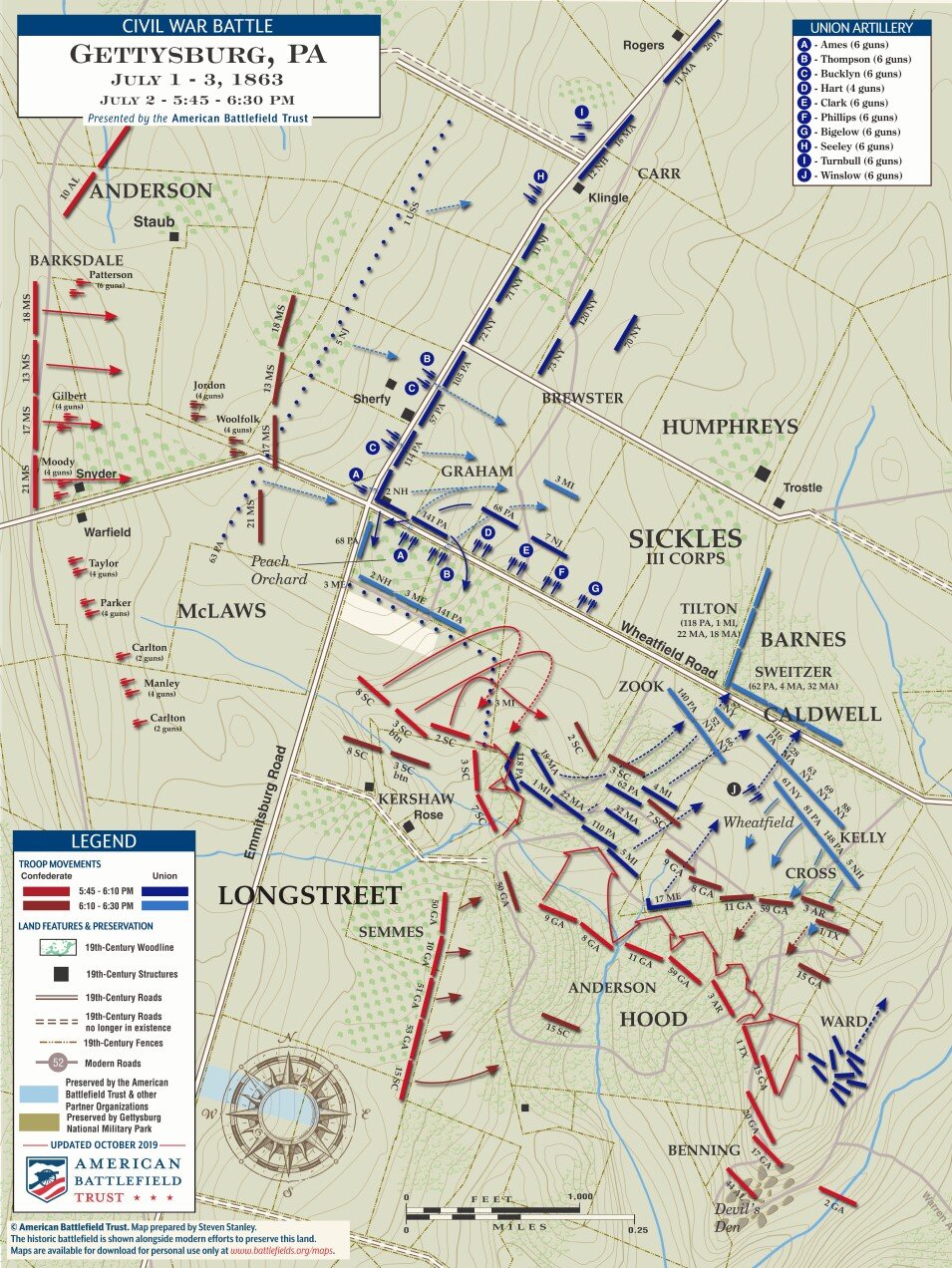

Walking southward along Cemetery Ridge toward Little Roundtop, I realized how the ridgeline “bleeds” into the landscape as it becomes less pronounced, and its defensibility decreases. The maps had not “spoken” to me, reading more than a few noted works had not sparked anything, but walking the ground became a revelation. Maps, histories, and terrain came together for me. Toward the ridgeline’s southern terminus, rising ground fronts it, and diminishes the effectiveness of defensive artillery. Rather than follow orders, and form a traditional linear defense, Sickles instead pushed his two divisions forward and established what were in effect brigade-strength strong points of around 1,500-2,000 soldiers each, fronting Emmitsburg Road, in the Peach Orchard, in the Wheatfield, along Stony Hill, on Houck’s Ridge, and in the Devil’s Den. Sickles’s decision infuriated Meade, but with a Confederate attack pressing it was too late to reposition the corps. Sickles’s unanticipated deployment, including a concentration of nine batteries of artillery, some fifty-two guns of varying calibers from III Corps and the army’s Artillery Reserve, along the higher ground at the intersection of Emmitsburg and Wheatfield roads broke up to the Confederate attack and destroyed unit cohesion even as the rebels destroyed III Corps. [6]

Walking that ground, taking in its subtleties, reading it, and interrogating it as I might a soldier’s letter home, or a general’s orders to his command, brought all the pieces together for me. The discussions between my students and with me were phenomenal. They ranged far and wide, and took in terrain analysis, engagement ranges, tactical formations, weapons effectiveness, tactical practices, a commander’s latitude in arranging forces, the limitations and opportunities afforded to subordinates by their superiors’ orders and intentions, leadership, bravery, and so much more. The discussions aimed at dissecting decisions and trying to understand and make sense of what past actors understood, how and why they acted as they had, and what the implications were for the present. I have led some twenty-five Gettysburg staff rides, and not one was ever the same, not one was ever run of the mill.

The Staff Ride

Staff rides are not field trips or tours. Indeed, they are more akin to research seminars or colloquia that depend heavily on student preparation, investment, and participation. The learning and teaching can be powerful, even profound. Traditionally, staff rides have been the focused study of a campaign or battle, but the methodology is equally applicable for physical sites linked to political, economic, cultural, and other considerations. Hence, they are inherently interdisciplinary, and easily incorporate aspects from other disciplines and colleagues ranging from “political science, international relations, law, literature, medicine…, philosophy,” and beyond. At their best, staff rides assist in understanding how past actors translated policy concerns and strategic guidance into tactical actions and how, in turn, tactical actions shaped and were shaped by the policy and strategy. They highlight the interwoven elements of war, warfare, and society, and the political, intellectual, cultural, and physical environments that enabled and constrained thought and action. Staff rides link the physical with the contextual through broadened evidentiary sources, through students’ reading and questioning participants’ accounts, secondary studies, and maps while on the ground, and, in turn, analyzing the physical environment. [8]

Staff rides might seem old-fashioned, “drum and trumpet” history. In a sense they are, but the need not be limited to that. Indeed, “it’s wise not to throw out the baby with the bathwater in our rush to embrace the newest evolutions in military history or in war and society studies. Tactical, and at a higher level, operational, movements are key to understanding the art and science of war and warfare. The topics—terrain, weather, the natural and manmade environments, army organization, tactical practices, weaponry, commanders’ knowledge at the time of the actions, their decisions, troop movements, the outcomes of battle, etc.—of a staff ride offer valuable insights into the nature of battle and the quotidian experiences of participants.” Walking and talking battlefields or other sites promote an empathy for those who existed in wars’ environments. As is the case with all teaching, individual creativity and imagination are the keys to going beyond the material at hand. Still, a bit of structure always helps. [9]

There are typically three-phases that constitute the staff ride, and they parallel more traditional classroom pedagogy. They are Preliminary Study (formal preparation), Field Study (the fun part, the site visit), and Integration (tying together learning, impressions, history, implications, and asking and answering the big “so what?” and “to what end?” questions). Ideally, the integration continues long after the staff ride as students reflect upon and draw from the experience. Preliminary Study and Integration will come most naturally and easily for teachers. Field Study poses the greatest challenge. It requires a familiarity with the physical environment equal to one’s familiarity with texts and evidence. It requires preparation by walking and exploring the locations and developing a comfort and familiarity with them equal to that with documents and texts. [10]

While nature and human activities will have altered much of the terrain, enough of it often remains for interpretation, analysis, and understanding. Often, there are reenactors or interpreters whose expertise and interests can assist in these processes through material culture and artifacts such as uniforms, weapons, and clothing, or by demonstrating period drill or other daily activities of the period. Witnessing interpretations and developing insight into the human relationship with the event and site can be evocative. In preparing for a staff ride, there are two handy references: The Staff Ride: Fundamentals, Experiences, and Techniques, published in 2020, and its 1987 predecessor, The Staff Ride, both published by the US Army’s Center of Military History, and available for download at no charge. The techniques fit battlefields or historic sites large and small. Size does not matter. [11]

Interrogating a Stand

A brief illustration is in order. One of my favorite staff rides is Charleston in the American War for Independence (the War for Independence is my specialization and Charleston is a wonderful place to visit). The ride is geographically extensive and encompasses James Island, Sullivan’s Island, Fort Sumter, and Charleston, from the Battery at the southern tip of the peninsula to just northwest of the Citadel. Because of the driving, walking, and the discussions, Charleston requires two full days to get the most out of it. Each stand (the location where you literally stand) requires about an hour to orient the students to their physical surroundings; for the student or students responsible for the stand to discuss what took place, where, when, and why the events happened, and what the participants perceived; and finally, for everyone to analyze the events, the people, and physical remains, and the implications, the “so what?” for the stand. Rather than run through all the stands, a closer look at one should suffice.

Fort Moultrie, one of the fortifications that guarded the seaborne approaches to Charleston, South Carolina, is a particularly good location to understand something of the relationship between land, sea, warfare, and society. What about its location? It guarded the North Channel, a secondary shipping approach to Charleston, but more importantly, Fort Moultrie covered the approaches from the main shipping approach, the South Channel. Warships and merchantmen were forced to approach the fort head on and sail under its guns. Until the invention of revolving turrets, this meant any approaching naval vessel had no meaningful firepower with which to defend itself or to attack the fort until it turned broadside. Fort Moultrie is on the southern tip of Sullivan’s Island, fronted by the Atlantic Ocean, with marshes and narrow, shallow waterways behind it. Mother Nature helped protect the fort. What of other fortifications, or did Fort Moultrie stand alone? In the eighteenth century, two palmetto-log redoubts (today reconstructed at Thomson Park) covered the northeastern tip of the island, the Breach, and protected the fort from an enemy attack or at least delayed it. [13]

James Wallace and Joseph F. W. Des Barres, “The Harbour of Charles Town in South Carolina, from the Surveys of Sr. Jas. Wallace Captn. In His Majesty’s Navy & Others, with a View of the Town from the South Shore of Ashley River,” The Atlantic Neptune (London: 1800), Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/gmd/gmd3m/g3301m/g3301pm/gan00003/an031040.tif, 21 July 2021

To the west southwest, across the shipping channel, stands what remains of Fort Sumter following extensive remodeling by artillery, courtesy of rebel forces and the US Army and Navy in the Civil War. In the War for Independence, it was the Middle Ground, a sandy shoal that endangered and channelized shipping. Fort Sumter, built atop a foundation of New England granite starting in the 1820s, guarded seaward approaches. Castle Pinckney, inside the harbor atop Shute’s Folly Island and to the northwest formed a part of the network of fire. Across the mouth of Charleston Harbor to the west southwest is Fort Johnson, overlooking a secondary shipping channel. In conjunction with Fort Moultrie, their guns were to form an interlocking field of fire able to strike enemy shipping from left and right. [15]

Discussions might ask students to consider the relationship between nature and the built environment. What did military engineers and others encounter? How did they incorporate and exploit the natural environment in their planning? What challenges might they have faced? How might an attacker have tried to develop a better understanding of the dangers and opportunities posed by the natural and constructed environments? Other questions might consider the artillery, their ranges, and how engineers and artillerists intended the various guns and fortifications to work together. They might probe matters as lowly as gun drill. How many soldiers manned the pieces? What entailed loading, aiming, firing, and resupplying each piece? In examining Fort Moultrie, students come to realize the threads of historical and military continuity that course through Charleston’s defenses, and that much of modern military practice is inextricably grounded in centuries’-old tactical considerations observation and fields of fire, cover and concealment, obstacles, key terrain, avenues of approach, and more.

There is, however, more to Fort Moultrie than strictly military matters. Potential lines of inquiry emphasizing a war and society focus might ask who built the eighteenth-century sand and palmetto fort and the nineteenth-century brick fort that today stands? Was it white wage-laborers, impressed Charlestonians, or a combination? Were laborers enslaved men impressed by the revolutionary regime or contracted by their masters for their own profit? Was it a biracial free and enslaved force? What laws sanctioned laborers’ employment? What were working conditions like? What of the skilled labor force, the brickmakers, masons, carpenters, and others? Were they free or enslaved? Where were the brick kilns and how were the bricks transported? What about the materials in the bricks? Where did they come from? These are but a handful of suggestions illustrating some of the vast possibilities in one stand, but also, importantly, reinforcing the connection between military history and war and society. Combined with other stands, the staff ride is a teaching and learning mosaic rich and profound with detail, nuance, and what historian John Lewis Gaddis termed selectivity, simultaneity, and scale. Context, historical and pedagogical, matters. [17]

Conclusion

All teachers realize that some of the best and most impactful learning (and teaching) comes from doing. A great lecture is just that; it is academic performance art at its best, and nothing can beat it. Discussions, small-group work, reading, writing, and research are all a part of the larger realm of teaching and learning history. Walking and talking the battlefield or other site through the staff ride, however, adds a new dimension to the enterprise of education by making the classroom and evidence one and the same. This most valuable element in the teacher’s arsenal, the staff ride, is but another way of enabling students to develop their historical mindedness by teaching them something different of the historian’s craft and thought processes.

Its origins as a vehicle for preparing officers to plan for and wage war notwithstanding, the staff ride offers teachers and students a singular method for expanding the boundaries of the classroom and archive. It is the meeting of academic and public history on the battlefield or other historic site. The staff ride’s interrogatory nature transforms the site into classroom and primary document open for study and informed conjecture. Much as when reading and considering a primary document, walking and talking the site requires students and teachers to exercise their imaginations, to use their minds’ eyes, and, to the best of their ability, to conjure the events and to place themselves in the sandals, shoes, boots, saddles, or tanks of those who were there, and to develop and appreciation for the interaction of humans and their environment. As with all aspects of history, the goal is to come to some understanding of a past world, its impact on the present, and implications for the future.

Author Leading the Cowpens, SC Staff Ride, “Post command teams relive history,” Karen Soule, Fort Jackson Public Affairs Office, 10 November 2011, US Army, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/images/2011/11/10/226412/original.jpg, 11 August 2021

My work as a military historian is inseparable from the staff ride. Indeed, the method has transformed me professionally. Walking and talking old battlefields with my students has helped me develop insights into some of the events and places that transformed soldiers’ lives, and often ended those same lives. Those past soldiers imagined and reflected upon warfare, the nature of battle, their manhood, and more. Their views evolved with the shock of reality. Walking and talking old battlefields has helped me develop a better, yet still imperfect understanding of their worlds, something I hope to convey to my students.

[1] “Richmond City: Tredegar Ironworks,” Richmond National Battlefield Park, https://www.nps.gov/articles/tred.htm, 20 July 2021.

[2] Although staff rides and tours are distinctly different, they do share some commonalities. See Thomas A. Chambers, Memories of War: Visiting Battlegrounds and Bonefields in the Early American Republic (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press) on the development of battlefield tourism in the United States. Staff rides continue as an element in professional military education in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and other countries.

[3] Ricardo A. Herrera, For Liberty and the Republic: The American Citizen as Soldier, 1775-1861 (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

[4] Bradley M. Gottfried, The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3-July 13, 1863 (New York: Savas Beatie, 2007), 143; “Detailed Strength and Casualty Numbers for the Army of the Potomac in the Battle of Gettysburg, Strength and Casualties—USA,” Stone Sentinels, https://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/battle-of-gettysburg-facts/strength-casualties-usa/, 6 August 2021.

[5] “Gettysburg—July 1 to 3, 1863,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/gettysburg-july-1-3-1863, 6 August 2021, courtesy of American Battlefield Trust.

[6] Bradley M. Gottfried, The Artillery of Gettysburg (Nashville: Cumberland House, 2008), 250, 252, 253

[7] “Gettysburg—The Wheatfield and Peach Orchard—July 2, 1863—5:45 pm to 6:30pm,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/gettysburg-wheatfield-and-peach-orchard-july-2-1863-545pm-630pm, 7 August 2021, courtesy of American Battlefield Trust.

[8] Peter G. Knight and William G. Robertson, The Staff Ride: Fundamentals, Experiences, and Techniques (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2020), 42, https://history.army.mil/html/books/070/70-21/index.html, 7 August 2021.

[9] Ricardo A. Herrera, “From Small Things: How a Staff Ride Became Two Articles and a Book Project,” Reflections on War and Society: Dale Center for the Study of War and Society Blog, University of Southern Mississippi, 11 September 2015, https://dalecentersouthernmiss.wordpress.com/2015/09/11/from-small-things-how-a-staff-ride-became-two-articles-and-a-book-project/, 18 July 2021.

[10] Knight and Robertson, The Staff Ride, 25-40.

[11] Knight and Robertson, The Staff Ride; William Glenn Robertson, The Staff Ride (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1987), https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/educational-services/staff-rides/CSI_CMH_Pub_70-21.pdf, 7 August 2021.

[12] “Sally Port, Fort Moultrie Today,” Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter National Historical Park, https://www.nps.gov/media/photo/gallery-item.htm?pg=838204&id=821CB6C4-1DD8-B71C-0731868BA65FD037&gid=821CB64D-1DD8-B71C-07A773A84AAA9999, 7 August 2021.

[13] “Fort Moultrie,” Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter National Historical Park, https://www.nps.gov/fosu/learn/historyculture/fort_moultrie.htm, 21 July 2021.

[14] James Wallace and Joseph F. W. Des Barres, “The Harbour of Charles Town in South Carolina, from the Surveys of Sr. Jas. Wallace Captn. In His Majesty’s Navy & Others, with a View of the Town from the South Shore of Ashley River,” The Atlantic Neptune (London: 1800), Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/gmd/gmd3m/g3301m/g3301pm/gan00003/an031040.tif, 21 July 2021.

[15] “Castle Pinckney, Charleston County (Shute’s Folly Island, Charleston Harbor,” National Register Properties in South Carolina, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, http://www.nationalregister.sc.gov/charleston/S10817710018/index.htm, 7 August 2021; “The History of Fort Johnson,” Marine Resources Center, Marine Resources Research Institute, https://www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/mrri/ftjohnson.html, 7 August 2021.

[16] W. A. Williams, Sketch of Charleston Harbor (Boston: L. Prang, [186-?), Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/gmd/gmd391/g3912/g3912c/cw0385000.tif, 21 July 2021.

[17] John Lewis Gaddis, The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 22-26.